Marine Salvage Operation, Grenville Channel, British Columbia

Zalinski

Coast Guard, Grenville Channel, British Columbia.

Setting moorings, Grenville Channel, British Columbia.

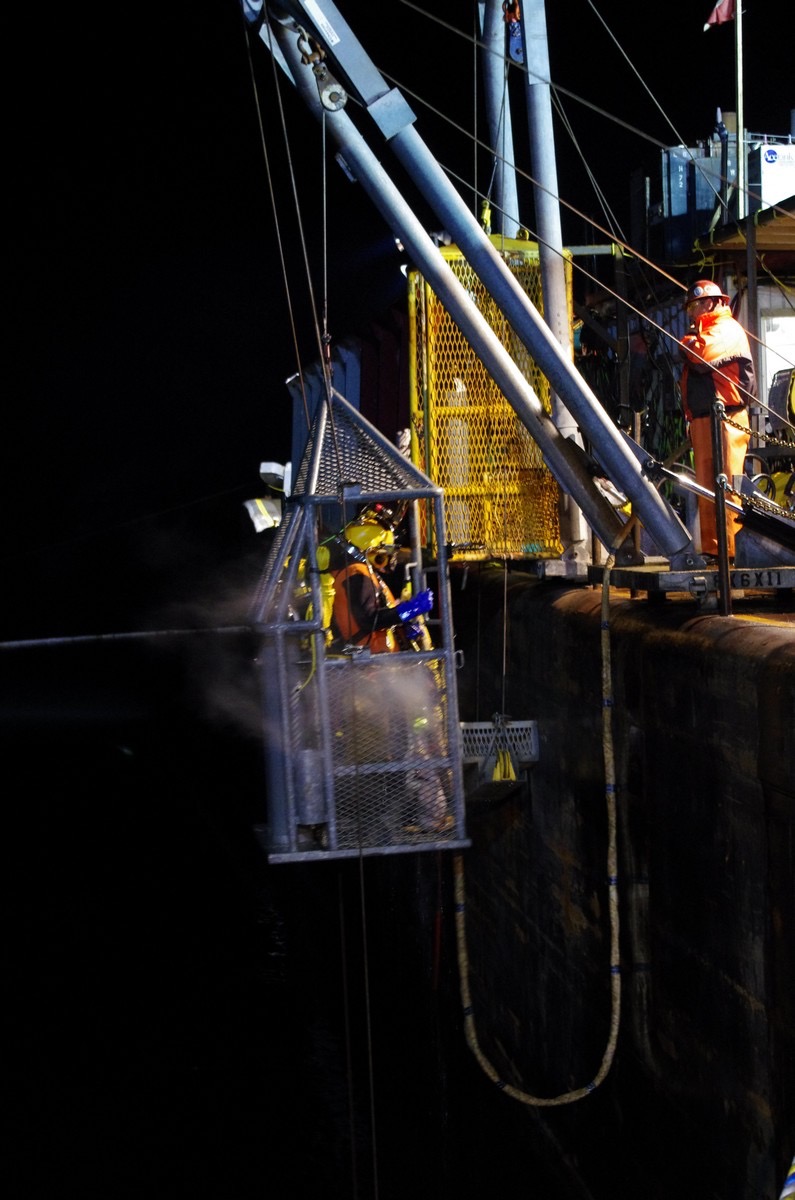

LARS (Launch and Recovery System) lowers a diver into the water.

Two Mammoet Crewmen and one Canadian Coast Guard on the tank top, in the rain, watching the pump returns (bunker oil) flow into the Baker tank.

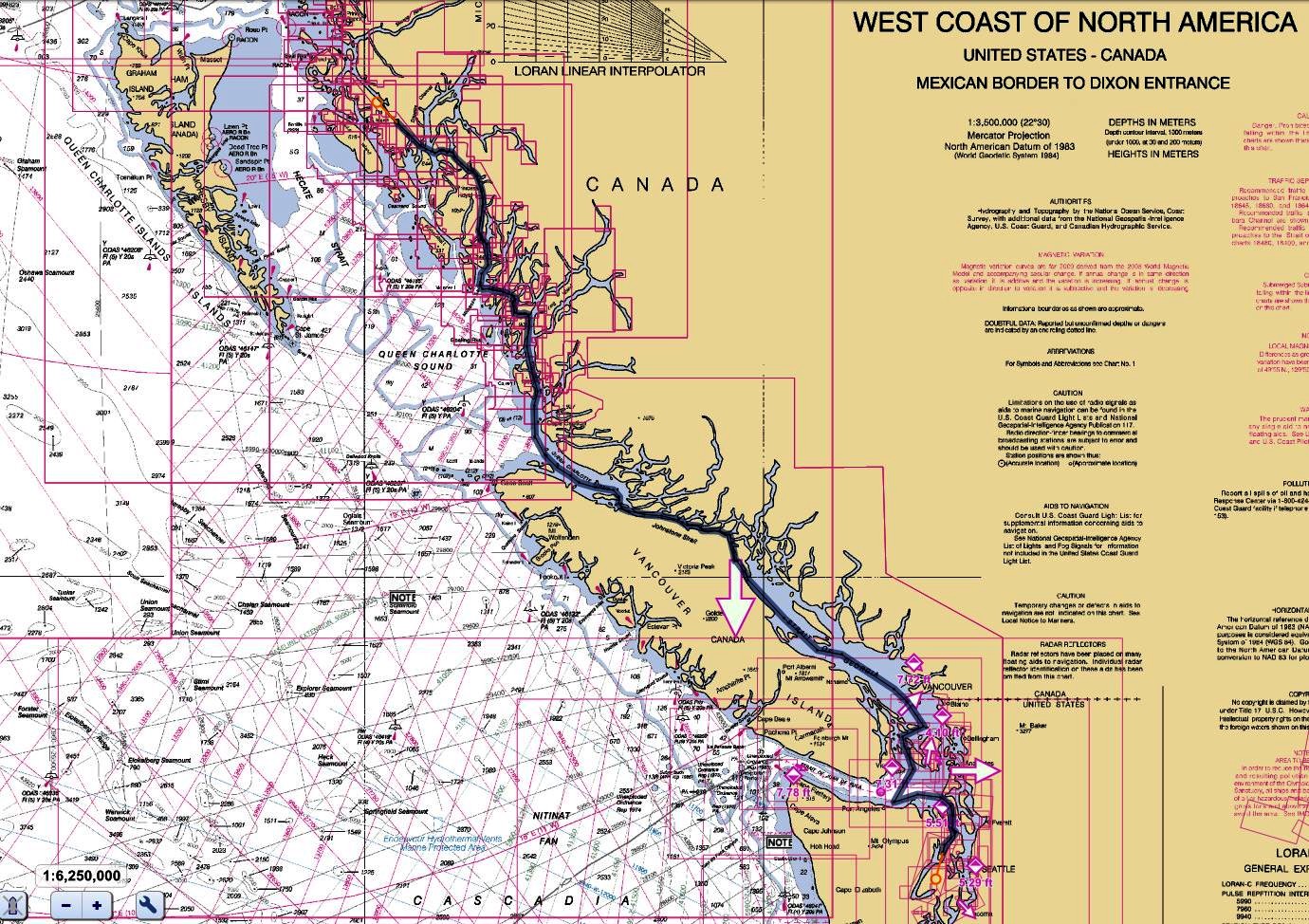

This is a chart of Zalinki's route, September 1946

Responsibility : Salvage Master

The Zaliniski Operation was an effort mounted in 2013 by the Canadian Coast Guard, to remove the fuel from the 1946 wreck of the American transport ship, USAT Brigadier General M.G. Zalinski. The Zalinski hit the rocks and sank in the Grenville Channel in British Columbia during a squall in the pre-dawn darkness, in September 1946 and was lost. She was not found again until the Canadian Coast Guard began searching for the source of mystery oil spills in the usually pristine waters of the Grenville Channel.

The Canadian Coast Guard landing craft pushed up against the steep rocky face. We scrambled over the bow to drag the heavy steel padeyes up to the relatively flat spots at the top of the rocky face where we planned to mount them, bolted to heavy threaded rod set in holes drilled into the solid rock.

The water was clear, and the rock face sheer. I could see deep into the water where the submarine rock wall was populated with sun stars, large white anenomies and clusters of tube worms and strands of bull kelp.

I had a picture of this sheer slate cliff in my mind when I read Captain Joseph Zardis’ account of feeling his ship, the USAT Brigadier General M.G. Zalinski hit the rock, tearing her open as glanced back into deep water. The scars of steel on slate were weathered away, but I knew that we were very near where she hit.

Zalinski’s Last Passage

It was reports of bad weather out in the open Pacific which had made Zardis decide to take the “Inside Passage” from Puget Sound to Whittier. His ship was heavily laden, carrying mail, munitions, trucks, food. At 2330 September 26, 1941 USAT Brigadier General Zalinski dropped her pilot at Port Angeles, and turned NNE to pass east of Vancouver Island.

Though protected from the weather, the Inside Passage is a demanding route. Without radar or depth sounders, pilots steered by compass and stopwatch; dead reckoning from point to point, taking bearings off lighthouses and prominent features of the landscape to get cross bearings to triangulate and make distance off and speed calculations. Poor visibility complicated pilotage, strong tidal currents, and darkness made it more difficult still. In the thick weather Zardis reported feeling his way along by sounding the ship’s horn, and listening for the echo off he rocky cliffs, a trick he likely learned from sailing ship captains feeling their way along the rocky steep-to coasts of the Pacific coasts of California and Oregon.

About 2300, September 28th, the Zalinski was passing Work Island. She had covered more than 500 miles since her departure. Zardis had been on the bridge for 18 ½ hours, piloting through the rock bound channels and passages. The visibility had deteriorated, the wind was southeast gusting force 6 to 7, with rain squalls sweeping across the area. Zardis slowed the Zalinski to half speed before handing the con to the pilot. He instructed the pilot to call him if the weather deteriorated further, and went to his cabin to sleep. Three and a half hours later, Zardis was awaken by the sound of the engine being brought back to full speed. He glanced out the porthole and saw that the weather had cleared. The Zalinski would have been coming around the south end of Gribbell Island. An hour and a half later, at 0358, Zardis was torn from his sleep Zalinski crashed into the slate wall which forms the eastern shore of Pitt Island, along the left bank of the Grenville Channel.

Soundings quickly established that the ship was sinking by the bow. Zardis gave the order to abandon ship at 0415. As the life boats pulled away, Zalinski was lost in the darkness and rain. By first light nothing was left on the surface but an oil slick and flotsam.

In the 1990’s the Canadian Coast Guard began to get sporadic reports of oil in the water in the southern Grenville Channel, in the middle of what the First Nations call the Great Bear Rainforest. Because of strong tidal currents, it took some years to establish that it was the wreck of the Zalinski which was leaking. In 2011 a Mammoet Survey Team ran side-scan surveys of the wreck and produced a report for the Canadian Coast Guard. In September 2013 Mammoet Salvage Americas was awarded the contract to remove the fuel from the wreck.

Naval Architect Han Schiet was tasked with finding the oil. Han had drawings of the ship. She was built in 1919 in Ohio for the Great Lakes trade, one of a class of more than a hundred built by the US Shipping Board at the end of the First World War. She was a riveted steel, coal-fired steamship named Lake Frohna (Hull number 765). In 1924 she was sold and renamed Ace, and became part of a small fleet known as the “Poker Fleet.” Her sister ships were named, “King,” “Queen,” “Jack,” etc. She was sold again in 1930, but kept the name “Ace.” In 1941 the US Army Transportation Corps bought her, and named her after Brigadier General Moses Gray Zalinski, a decorated veteran from World War I who died in 1937.

Somewhere along the line the ship which would become the Zalinski was converted from coal to oil. Some of the tanks originally designated as feed water tanks were likely converted to carry oil, as well as some of the coal bunker tanks, but Han had no “as built” plans. He studied the original plans, and as a naval architect tried to think of how he would have converted her. Then, based on those guesses, and the position of the wreck on the bottom, he laid out a program of test drilling to test his assumptions.

When the divers began to test drill on the wreck, some of what Han guessed proved true, but there was also oil where there shouldn’t have been. Han decided that divers needed to get inside the forward hold to inspect the bulkheads and tanktops, see if they were still intact.

Global Diving, Mammoet’s dive contractor on the project, had brought a VideoRay, a small inspection ROV. The divers cut a hole in Zalinski’s side shell just large enough to insert the ROV for the internal inspection.

Unfortunately, nobody had counted on the wreck being the home of a 2 ½ meter Giant Pacific Octopus. As soon as the VideoRay’s lights were switched on, and it was launched through the hole in the ship’s side, the octopus captured it, and hauled it away into the farthest corner of the hold. The divers had to cut a hole large enough for a diver to go and rescue the VideoRay. When the diver got inside, he saw that the forward bulkhead had wasted away completely. The distinct tanks, which were part of the original structure of the ship, and part of the plan for removing the oil, were gone. The bunker fuel which was left was migrating freely into the highest points of the upturned hull.

Based on the new information, Han changed the test drilling plan to include areas not part of the original tankage. The test drilling showed that not only had the oil migrated into unexpected areas, but that there was a lot less than the 400+ tons the bid was based on. With the Coast Guard informed of the findings, the Coast Guard and Western Canada Marine Response Corporation (WCMRC) mobilized their response boats to be on location in case of a spill as Mammoet and Global Diving hot-tapped the hull in multiple locations, and began pumping off the oil. Being as cold as the surrounding water, the Bunker C fuel oil flowed like cold molasses.

The team pumped each of the hot tap points until the returns were mostly salt water. After the first round of pumping, the team made a second round, pumping until the visible pump returns showed only trace amounts of oil.

There was recognition with the Canadian Coast Guard that over time the oil left in pockets scattered through the wreck would migrate to the high points in the hull, to the Mammoet hot-tap points, and to that end Mammoet was requested to leave the hot-tap valves in place so the wreck could be revisited, and additional oil which had collected could be pumped off.

As far as the Giant Pacific Octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini), the ROV was not the first encounter. Diver Alan Deaver was on the wreck one night early in the project when he saw the octopus swimming toward him. “I used to work at the Monterey Bay Aquarium and have worked a lot with octopus,” he said. “I recognized that it was a dofleini, and they are not aggressive, just very intelligent, friendly and curious. He came right up to me and wrapped himself around me, feeling my helmet and regulator, checking me out. I’d have liked to spend some time playing with him, but they’re paying me to work, so I just peeled him off and gently shooed him away.”

It was during the final stages of pumping, in a mixture of snow and rain, that Roger Girouard, a retired Rear Admiral in the Canadian Navy a and the Canadian Coast Guard’s Assistant Commissioner, Western Region, brought a delegation, including the First Nations representatives, to see the operation first hand, to look at, touch and smell the oil which the team had pumped from Zalinski. “Not only has the pollution risk been removed,”Girouard said, “but it was done safely. From the beginning I said that nobody was hurt the night the Zalinski sank some 70 years ago, and we weren’t going to hurt anybody now. We haven’t, in spite of some very difficult conditions at times. Credit for that, and for the success of the project, goes in no small part to the teams from Mammoet Salvage and Global Diving.”

Have A Marine Salvage Project?

With 30 years of experience, Porter Marine Salvage & Consultancy provides expertise in all aspects of marine salvage operations.

© 2017, Dan Porter